By: Richard Kuchinsky © The Directive Collective

As any good chef knows, the secret to good food is good ingredients. In footwear, the same is true.

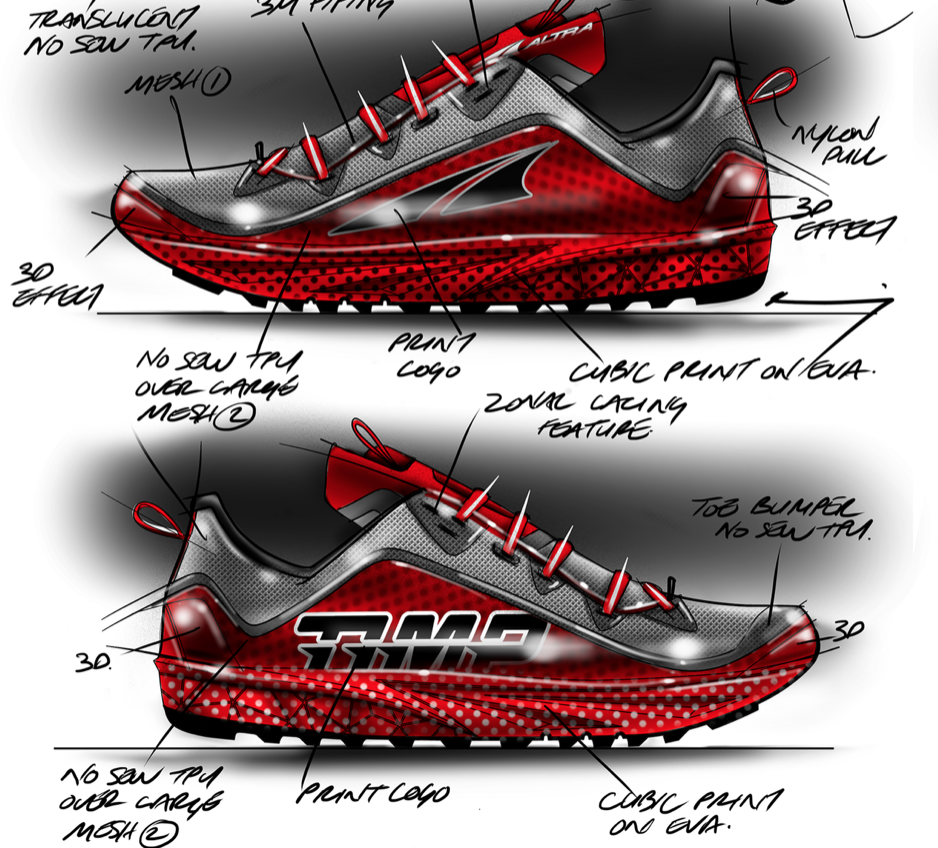

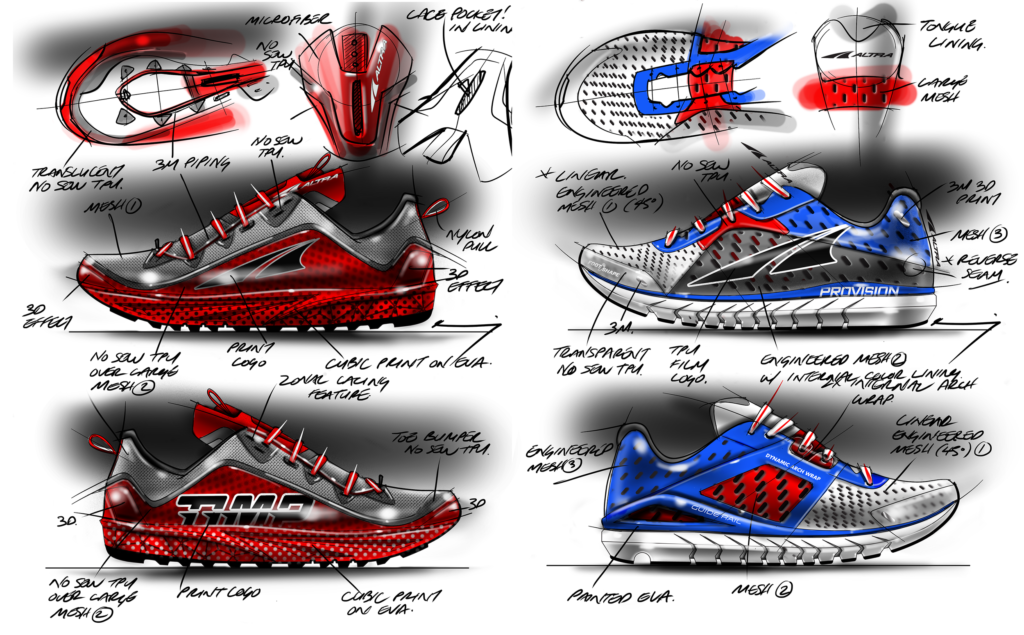

As a runner and running shoe designer, understanding materials is probably the most important part of my work.

Like food though, the ingredients are only good if you know what to do with them. Not everyone is a Michelin star chef just because they have a bottle of truffle oil in the pantry.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say most bad shoes are bad because of bad material design. Using the wrong material can affect comfort, performance and the consumer’s experience.

Good design is understanding a variety of materials and leveraging the right material for the right application.

Picking the material type is always about compromise. Knowing what is more or less important drives material choice. There is no one material that is good at everything.

Is high performance energy return top of the list, or is it sustainability? Price? Durability? It’s virtually impossible to have it all, equally. Making the material choice that matches the project brief is a skill and takes a deep understanding of what materials are available and the benefits and tradeoffs they offer.

In super shoes for example, PEBAX is often used for incredible energy return and light weight. But with that comes a very high cost and complexity to processing and molding plus durability issues. Expanded TPU can give a similar (but not quite as good) bounce and longer life, but it’s heavier and doesn’t perform as consistently at different temperatures.

Once a material type is selected it’s also key to dial in the specification. Specification can affect both consumer facing experience and the quality of the product.

Specification can loosely be separated into physical property performance and mechanical properties. Physical property includes performance characteristics such as density, hardness, and durometer for a foam. Mechanical properties might include tensile strength, elongation, tear strength and compression set. Both are important to know how a material will perform today and if it will last tomorrow.

Even so, just using the right material and the right specification isn’t all that matters and it’s far too easy to get hung up on materials and specs.

Design needs to leverage those material benefits and specifications to make the most of them.

In my experience, design for material is one of the most difficult challenges I face with my clients.

Committing to a base material and spec plan up front at the brief stage and building a design around it is the best way to ensure success. Design and materials must go hand in hand. You can’t design first then randomly pick materials.

Changing materials because of supplier pressure or fiddling with a spec last minute to appease sales without adjusting the design to match can cause huge problems. I’ve seen great designs turn into dogs because someone wanted to save $1 per pair or wanted to skip opening new molds.

Even with I have a huge library of samples, swatches and reference catalogs I’m always on the search for new materials, processes and suppliers. I take meetings weekly with new potential suppliers and browse trade journals and publications to keep on top of research and innovation.

Still, any time I hope to use a new material in a project I always warn the client that it will take extra time and cost. There’s cost for swatches, samples and application trials. Test molds and tooling. Set-up costs and lab tests. Time to learn how to best use that material.

Material innovation can make a huge difference to performance and project outcome but it takes a real willingness support the process and a designer to enable it.

Resource: https://www.directivecollective.com/blog/materials